A large variety of basketry has always formed part of the material culture of the sedentary Bantu-speaking people of Namibia, e.g. the AaWambo, VaKavango and inhabitants of the East Caprivi. Nomadic hunter-gatherers and herders, who had to limit their material possessions to what they could transport, could not afford to have such a wide variety of basketry. With the exception of the Khwe, who manufactured their own baskets, most San groups traded their baskets from Bantu-speaking neighbours.

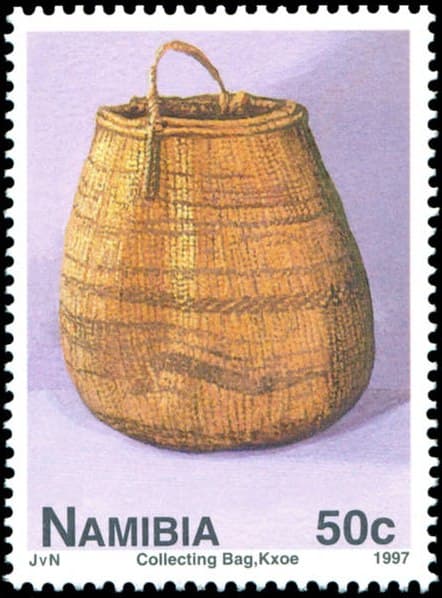

Collecting Bag, Kxoe [Khwe], 50 Cent, issued in 1997, artist: Johan van Niekerk

The Khwe, who live in the eastern section of the Hambukushu area of Kavango, in the West-Caprivi and areas bordering the Kwando River, are generally classified as San, although their language, their physical appearance (they were sometimes referred to as 'black Bushmen') and their history differ distinctly from e.g. the !Xun, who live further south. Long before the Khwe moved to their present area, they lived in close contact with Bantu-speaking neighbours, e.g. the Luyi-Balozi in a region east of the Zambezi River, which resulted in their dark complexion and their stronger body structure. More recently, they mixed by marriage with the Nyemba and HaMbukushu in southeast Angola and the Kavango area and until the early 20th century they often acted as their servants. As a result of the historical contact with Bantu-speaking tribes some objects of the material culture and agricultural practices, as well as the acquaintance with stock penetrated the life sphere of the hunter-gathering Khwe.

In former times, the Khwe made flat winnowing trays, cone-shaped pópò-baskets and bag-shaped /oámà-baskets. They were made according to the coiled technique and a type of vertical coil. During the process of manufacture the makers, who were women, used bundles of strong Aristida grass stalks, which formed the core of the coil, and the middle leaf of the makalani palm (Hyphaene petersiana). If these were not obtainable, the leaf of the Phoenix reclinata palm was used instead. In order to make the palm leaves soft and flexible, they were soaked in warm water before the basket making process commenced. Sometimes the palm leaves were also coloured in different shades of brown by boiling them with the pounded bark of Berchemia discolor. Women made /oámà-baskets until the early 1960s. They were also regarded as their owners. Their height varied between 12 and 30 cm and they always had a handle of skin or fiber. They were primarily used as collecting baskets and for storing berries and other bush crops. When wild fruits were collected these were first collected into smaller pópò-baskets and poured from there into the /oámà-baskets. Popo-baskets were also used for winnowing grain.

The ethnological collection of the National Museum of Namibia is in possession of several /oámà-baskets, as well as a pópò-basket, which were collected in 1932 in the West-Caprivi and finally made their way into the museum’s collection in 1948. According to Professor Dr Oswin Köhler, who started with the documentation of the culture and language of the Khwe as from the early 1960s, the making of /oámà-baskets had died out during those years although he still found some examples, which were used. He was able to photograph them and record some interesting information on basket making from his informants. Older people still had the knowledge to make /oámà-baskets although they did no longer produce them. Pópò-baskets were still made.

In 1996, Khwe basket making was revived with the support of a national craft promoter looking for marketable crafts to advance income generation. Since then, the Khwe again make /oámà-baskets not only for their own use, but primarily for the tourist market. Modern /oámà-baskets are sold at a local craft outlet at Kongola and various other Craft Centres in the country. The manufacturing technique and shape of the baskets are similar to the traditional ones although they are generally smaller and have more elaborate designs and more robust handles.

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT