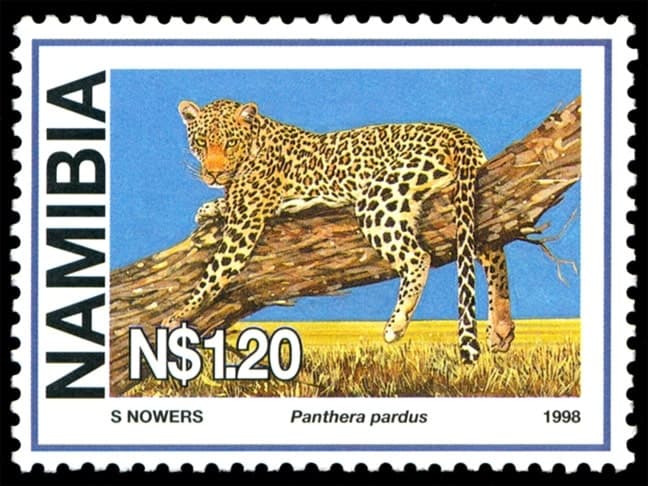

Beauty and power blend seamlessly in Panthera pardus, an animal that seems to have been given a double share of both. As the leopard emerges from a thicket, blending into the dappled light and pads across the leafy earth to disappear once again into the vegetation, the observer cannot help the quickness of breath or the feeling of awe he experiences for this fleeting vision of the ‘prince of stealth’.

Solitary and predominantly nocturnal, the elusive leopard (luiperd in Afrikaans) is rarely seen. Once having a wide distribution including Africa and the Arabian Peninsula through south-western Asia into India, China and the Russian Far East, the leopard’s range has shrunk considerably over the years through hunting, persecution in farming areas and loss of habitat. It is listed as near-threatened on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Red List. Although it has disappeared from 36.7 percent of its historical range in Africa, is on the verge of extinction in North Africa and survives only in fragmented populations in some parts of its range, it is still widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, managing to endure in areas where many of the large cats have not.

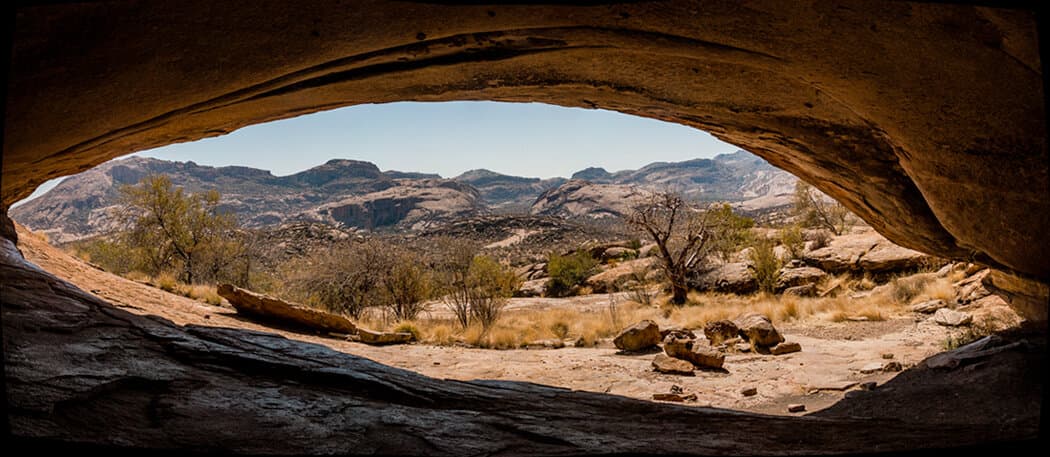

There are nine sub-species of Panthera pardus worldwide recognised by the IUCN, living in a wide range of habitats from rainforest to desert, where there is sufficient cover for concealment. The leopard is not dependent on water, obtaining moisture from the body fluids of its prey, but will readily drink if water is available. In Namibia, it is found throughout the country but prefers areas with rocky outcrops and mountains. It marks its territory using scratching posts and urine spray.

The smaller of the Panthera ‘big cats’, the leopard, with its rosette markings, relatively short muscular limbs, a long low-slung body and large skull with powerful jaws, is an opportunist feeder. Its diet includes anything from dung beetles, dassies, francolins, carrion and black-backed jackal to medium-sized and occasionally large antelope. It has even been known on the rare occasion to feed on crocodile. Secretive, well-camouflaged and silent, it hunts by stealth, stalking its prey with patience until close enough to pounce, taking it by surprise. To protect its kill from other predators, the leopard carries it up into a tree, or drags it amongst rocks or under dense bush. In areas where its natural prey has been eradicated, it may prey on domestic stock and has proven to be a menace in farming areas.

Leopards unite to court and mate and litters of 2-3 cubs are born after a gestation period of 100 days. The female hides the 500 g cubs in dense cover or rock crevices, out of danger. The cubs stay with their mother for 18 months, learning to hunt and fend for themselves. While on the move, they follow the white tip on her tail which serves as a beacon.

Half the size of a lion, the adult leopard standing at 80 cm is a formidable 50-90 kg powerhouse not to be trifled with. (The male is larger than the female with a heavier thick-set head.) Usually shy, however, and sensitive to noise, it will quickly disappear when there is a disturbance. It is only known to attack humans when trapped, threatened or injured, preferring the flight rather than the fight response to danger.

Its low rasping and rhythmic grunt-like call, likened to the sawing of wood, alerts Etosha visitors to its presence at a waterhole before it makes its rare appearance from out of the darkness. In areas where there is little human disturbance it can sometimes be seen in the cooler hours of the day padding along a dry river course or through the long grass, offering a fleeting opportunity to witness ‘the embodiment of feline beauty, power and stealth’.

Contact for collectors: Philately Services, Private Bag 13336, Windhoek; Tel +264 (0)61 2013097/99, philately@nampost.com.na

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT