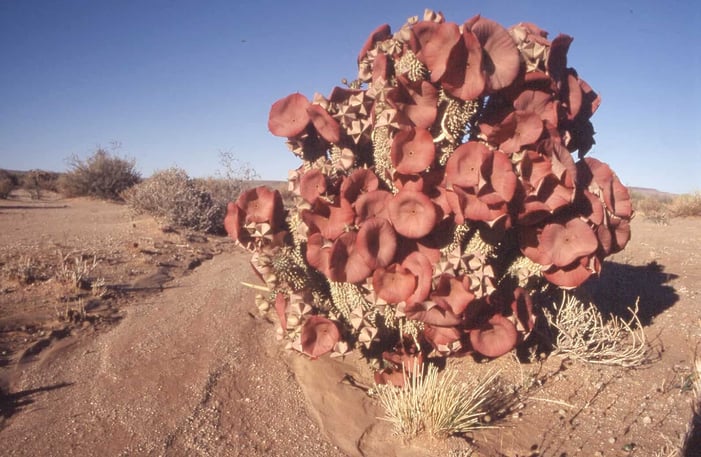

A true desert bloom crowned in the springtime by large disc-shaped crimson flowers, Hoodia has received much attention over the years, not for its ability to store moisture and thrive in arid areas or for its exquisite blooms but rather for its use as an appetite suppressant. In the last decade it has been universally acknowledged that the San/Bushmen, the oldest inhabitants of southern Africa, own the rights to the indigenous knowledge of the plant, but that has not always been the case.

The plant was used by the San for millennia as an appetite suppressant and thirst quencher (also as a treatment for high blood-pressure, diabetes and as a cure for abdominal cramps, haemorrhoids, tuberculosis, indigestion and hypertension), long before it was sought after in a western world in its battle with obesity.

The species of most interest in the family Apocynaceae for its appetite-suppressing qualities is Hoodia gordonii found predominantly in southern Namibia and north-western South Africa. The spiny-stemmed succulent grows in gravel or shale plains, Kalahari sands or on dry stony slopes. It can tolerate temperatures exceeding 40?C and as low as -4?C. Incredibly, a single plant can have as many as fifty branches growing from its base, can grow up to a metre high and weigh as much as thirty kilograms. Although eye-catching, the flowers referred to as stapeliads, are only attractive to its pollinators - flies and blowflies - with their strong carrion-like odour.

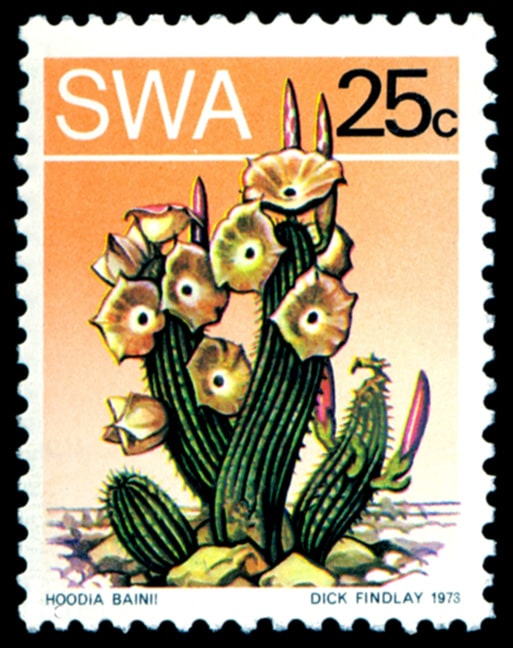

The first Europeans to encounter Hoodia gordonii were Paterson and Col RF Gordon, who in December 1778 found specimens in the Upington area. Botanist, Francis Masson, recorded the use of Stapelia gordonii on his visits to the Cape around the same period. It was later transferred into the Hoodia genus, so named after dedicated succulent grower, Van Hood.

Hoodia is a protected plant in Namibia and a permit is required from the for cultivation or harvesting, relocation or trade. It is also listed on the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES), Appendix 2, regulating international trade.

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in South Africa began to include Hoodia in its projects as early as 1963 and in 1995 it filed for a patent application for use of the active components (it had isolated the active compound - P57) responsible for appetite suppression. It later signed licensing agreements with UK pharmaceutical company Phytopharm that in turn sub-licensed the rights.

In June 2001, a South African-based NGO, Biowatch South Africa, with assistance from the international NGO, Action Aid, alerted the foreign media to the fact that the San had not been involved in the development or commercialisation of the Hoodia products, leading CSIR to enter into negotiations with the San. They were represented by the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA), the South African San Council and the San Institute of South Africa (SASI). This culminated in the CSIR and the South African San Council signing a benefit-sharing agreement in March 2003 with the San receiving a percentage of the royalties.

In August 2004, the San Trust, formally named the San Hoodia Benefit Sharing Trust, was registered, with 75 percent of all Trust income to be equally distributed to the San Councils of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa.

The bottles of weight-loss products lining pharmacy shelves have little resemblance to the hardy desert plant that survives in the Namib Desert, its soft sensual bloom belying its tough existence, and its recent history is far removed from the time when the San still freely lived off the land and roamed the southern sands of Africa.

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT