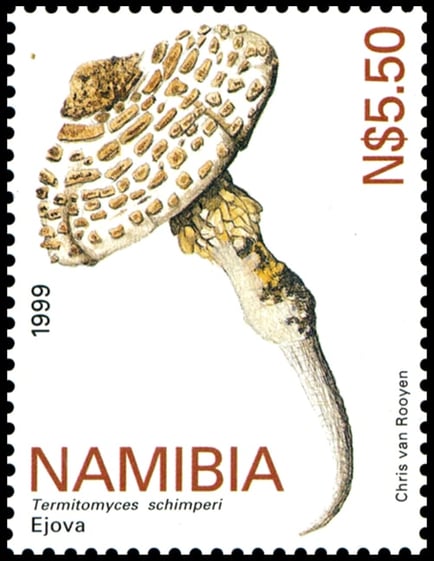

Towering termite mounds reaching heavenwards from the savannah characterize many areas of Namibia. Adding to the visual impression created by the striking insect homes, giant mushrooms emerge from the base of the mounds during the rainy season. As the grass turns green and the clouds mass for summer downpours, the gargantuan fungi appear as if in celebration of the rains or as manna from the gods.

Omajova is the commonly-used Herero name for these termite hill mushrooms that are harvested by the locals, supplementing diets and incomes. The wild mushrooms which can weigh in at a kilogram apiece are heavyweight contenders in the fungal arena, far outweighing the supermarket variety. Although they have their own unique flavour, like their more conservative cousins they are best cooked in butter and salted.

The enormous mushrooms are cultivated by termites. At certain times of the year, usually after the first rains, reproductive alate (winged) termites emerge from the nest to start their own colonies. After a suitable nest-site is found by the male and female termite pair, they lose their wings, mate and start to lay eggs. Besides the royal pair, the termite colony will also comprise soldiers and many industrious workers. When the ‘flying ants’ emerge from the mounds en-masse, they are often collected by people in rural Africa, considered as a delectable food-source.

Termites build their termitaries from mud and saliva moulding ingenious ventilation shafts above their subterranean nests to maintain a constant temperature, mastering perfect environmentally-sound housing systems. The Macrotermes (fungus-cultivating termite) colonies have a symbiotic relationship with the fungus Termitomyces. The termites cultivate the fungi in a fungus garden, a collection of fungus combs made from chewed-up grass and wood collected by the termite foragers. The fungal spores germinate and grow, converting cellulose into simple sugars (and nitrogen), making it more readily digestible for the termites. Fresh material is added to the top of the fungus combs as the digested material is consumed. The symbiosis provides optimum conditions for both; a safe haven for the fungi and pre-digested food for the termites.

Every year, after the onset of heavy rains usually in late January, February or March, the fungus comb sprouts a number of stems that penetrate the hard soil of the mound producing fruiting bodies, referred to as termite-hill mushrooms or Omajova, which erupt from the base of the castle of sand.

The small insects play an important part in the ecosystem by breaking up organic plant material and the interior of abandoned termite mounds provide subterranean homes for animals like snakes, mongoose, porcupine, aardvark and warthog. The mounds themselves make good observation points for a variety of animals to survey the surrounding countryside.

Like the Kalahari truffle and mopane worm, the Omajova is an intriguing Namibian delicacy. At the time of year when the sky is often dark with rainclouds, Omajova sellers display their wares alongside the road or hold them up like huge fungal flags to attract passing motorists. They can often be seen outside Wilhelmstal en-route to Karibib and on the road to Tsumeb. For the best purchase, the closed or young fungi have less chance of harbouring sand or insects although the open fan-like milky crown is an enticing bloom.

Whether eaten à la crème, fried with asparagus and cherry tomatoes, in an omelette, crumbed or wrapped in slivers of salmon, the mushrooms provide a tasty treat, courtesy of the African savannah, to be enjoyed in the bountiful season of summer.

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT